Jerwood Gallery, London - 1999

Jason Brooks, Benedict Carpenter, Anya Gallaccio, Jim Hodges, Virgil Marti, Jason Minsky, Jo Mitchell, Simon Periton, Jean Noel Rene Clair, Bridget Smith

Text by David Barrett

A Pointless Existence We must begin by looking at nature. Not the constructed versions that we have surrounded ourselves with, but the brutal, unreconstructed nature that existed before we imagined it. This can be difficult to do; so used have we become to reading meaning into 'sublime' landscapes, or message-laden flowers, or demonic reptiles - everything is so significant - that it is difficult for us to come to terms with the utter senselessness of nature.

We are creatures that deal continually, consciously and unconsciously, with the play of meaning. We assign it to everything, and there is nothing to us which is devoid of meaning. Ironic, then, that in order to mask the pointlessness of our own existence, we simply refuse to recognise the blunt senselessness of all nature. Is our existence really pointless? We are, on the whole, a society without religion, and without religion there is no meaning to be found in the universe or its inhabitants: it is a truly meaningless domain. Sure, we understand how nature operates - Newton, Darwin, Einstein, Watson & Crick told us this - but as for why... well, that is a question that cannot be answered without recourse to metaphysics.

To show how much we assume meaningfulness in the world, simply count how many times ! have to use words that end in '..lessness' throughout this essay. This proves that the natural state - that of a lack of meaning - is automatically expressed as a negative, that is: the opposite of the assumed state.

But surely we do find meaning in nature? Well, yes, a semiotic study of nature will reveal a myriad of signified meanings - red roses mean love, oak trees mean ancient dependability, etc. - but these meanings have merely been projected onto nature by humans. Such connotations are in no way innate.

This is not to say that our actual living spaces are also empty of reason. Quite the opposite; our urban environment is totally designed, every inch of space the product of conscious thought. And this is the point. Urban dwellers find it difficult to believe that there are places in the world where things have simply grown, rather than having been planted or introduced or protected. We stretch a layer of metaphors over nature to protect us from its stark senselessness. Pulling away this shroud of meaning reveals the universe for what it is: an accidental, pointless playing-out of mechanical rules. And our consciousness has always had a problem with that.

The Rise of Simulation So the function of our constant generation of meaning, of assigning significance to objects, is to protect our psyches from the uncomfortable truth of meaninglessness. And this helps us to understand the well-documented drive towards virtual realities, controlled environments and simulation. In a sense, the perfect worlds we produce are merely an attempt to play the part of God, now that He is no longer here to guarantee meaning. (i)

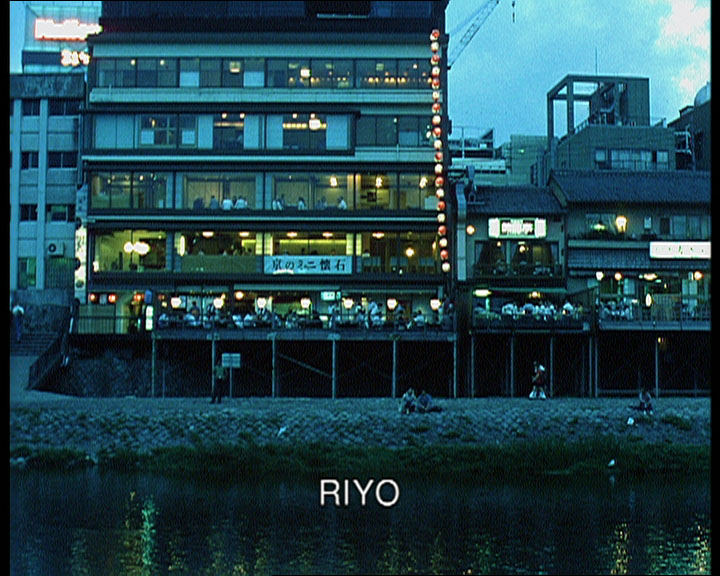

But it is not simply perfect environments we're after. No; they are simply a consequence. The real perfection that we crave is a perfection of meaning, of signs. Everything should look exactly how we expect it to look, and no different. It is not perfect nature that we want, but perfect signs of nature, that is: nature acting as a sign for itself. We have produced a fairytale universe where each element simply presents the connotations that we expect it to have. A world where we can be sure to instantly recognise everything, and everything is precisely what it seems to be. No shocks, no alarms, no surprises. Just archetypes. A grotto should be magical, a golf-course should be lush, a biker-girl should be sexy (but in a retro, non-threatening way). Pure signifiers. Both Bridget Smith and Jo Mitchell know this.

Consider Benedict Carpenter's Flocked Objects. These Rorschach blots - epitomes of the ambiguous and unknown - become crystallised into physical objects. The unknown is exorcised through a process of visualisation. Every Horror-film director knows that a monster is only scary when you can't see it. The Flocked Objects control the unknown by presenting it to us in the cold light of day. We can begin to rationalise the objects, pin meanings onto them, discuss them. What's so scary about that? Precisely nothing.

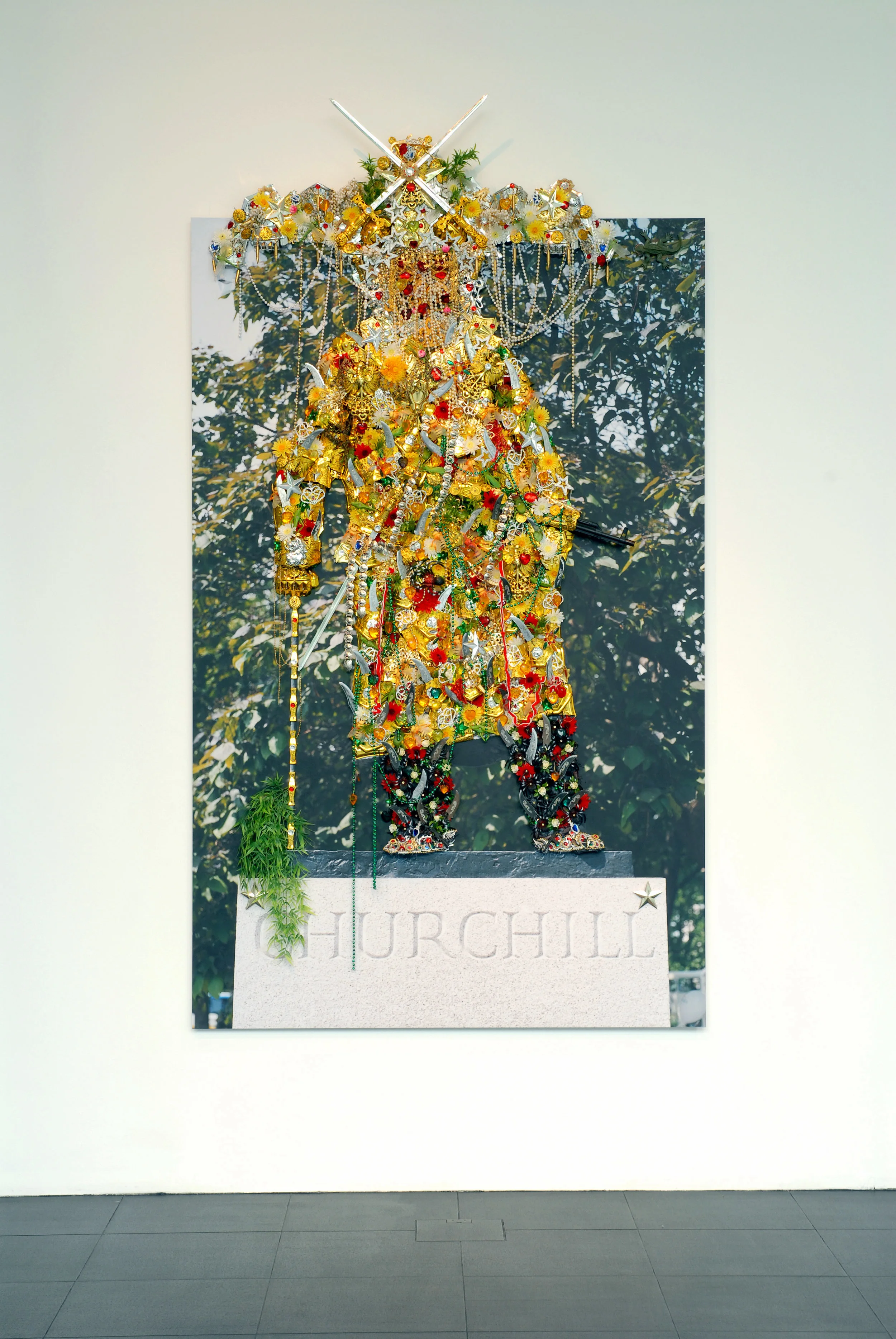

There is no end to this seamless fiction of meanings. Even pure signifiers like the Nike Swoosh are just another part of our environment, as Jason Minsky's Victory shows, just as his picnic hamper/air purification plant Breathing Air suggests that the oxygen we breathe ought to be manufactured by chemical apparatus. Everything is re-designed, re-made, re-presented, re-duplicated. (ii)

Of course, no life can grow from this claustrophobic fiction; the violent, chaotic animal-exuberance of creation has no place here. Our quest for hermetic meaningfulness is stifling, just like You: Jim Hodges' silk flower curtain. Perfect, beautiful and utterly lifeless. Not dead, of course, because the concept of death presupposes life. This is just lifeless, that's all.

Controlling Excess So our controlled simulacra deny the irrational, the chaos of meaninglessness, make it a taboo. Everything is a perfect sign for itself in this sanitised, corporate-endorsed reality. There are no unwanted ideas. But this is an uncomfortable truth, we don't want to believe that our world is quite so stifling. This is why we crave absurd fantasies like Disneyworld: building a crude, obvious fake makes our everyday simulacra appear more convincingly real.

Simulation is the culmination of the need to bracket our universe within the realm of reason, of work, of production and consumption. Simulation is against violence. And yet excess - and the transgression that this implies - is required to justify such all-encompassing reason (why would we need reason, logic and order if there was not chaos and meaninglessness?).

So the rationalisation is here to protect us from the violence of animal irrationality. But since we are created from precisely such irrationality, we find such unending orderliness asphyxiating. In short, we need a vent to let off steam, hence our little moments of transgression are prescribed. (iii) Which is why it's okay for Jean-Noël René Clair's idealised photographs to lapse into pornography. In fact, it's required.

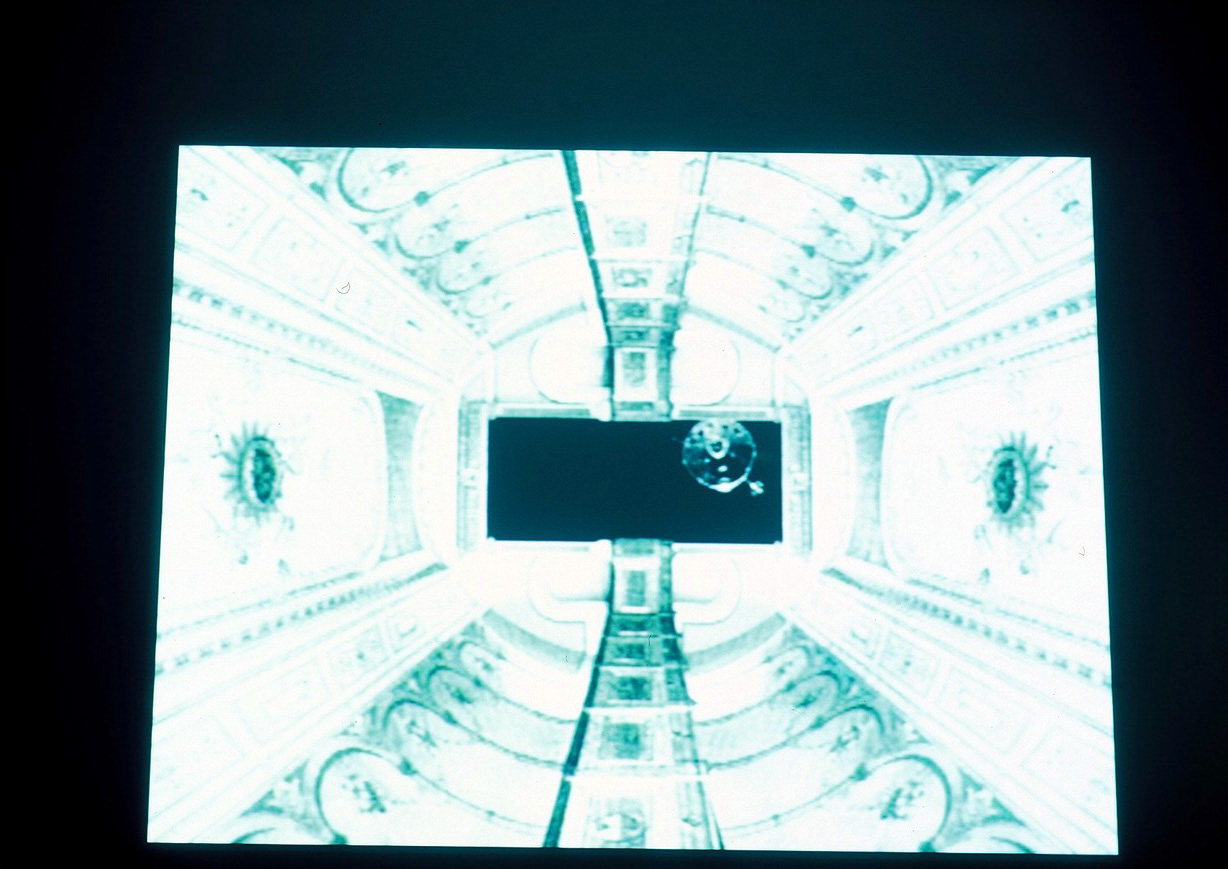

Spiralling Simulations in a Closed Loop But in this digital age, where universes are constructed entirely within rational systems, where is the vent? There is nothing in these systems that hasn't been put there for a precise purpose. There is no vent. The system is a closed loop. It spirals into vertigo, producing its own excess, reaching its own ecstasy. No growth. No future. No past. Just an endless contemporary instant, buzzing with overloaded information.

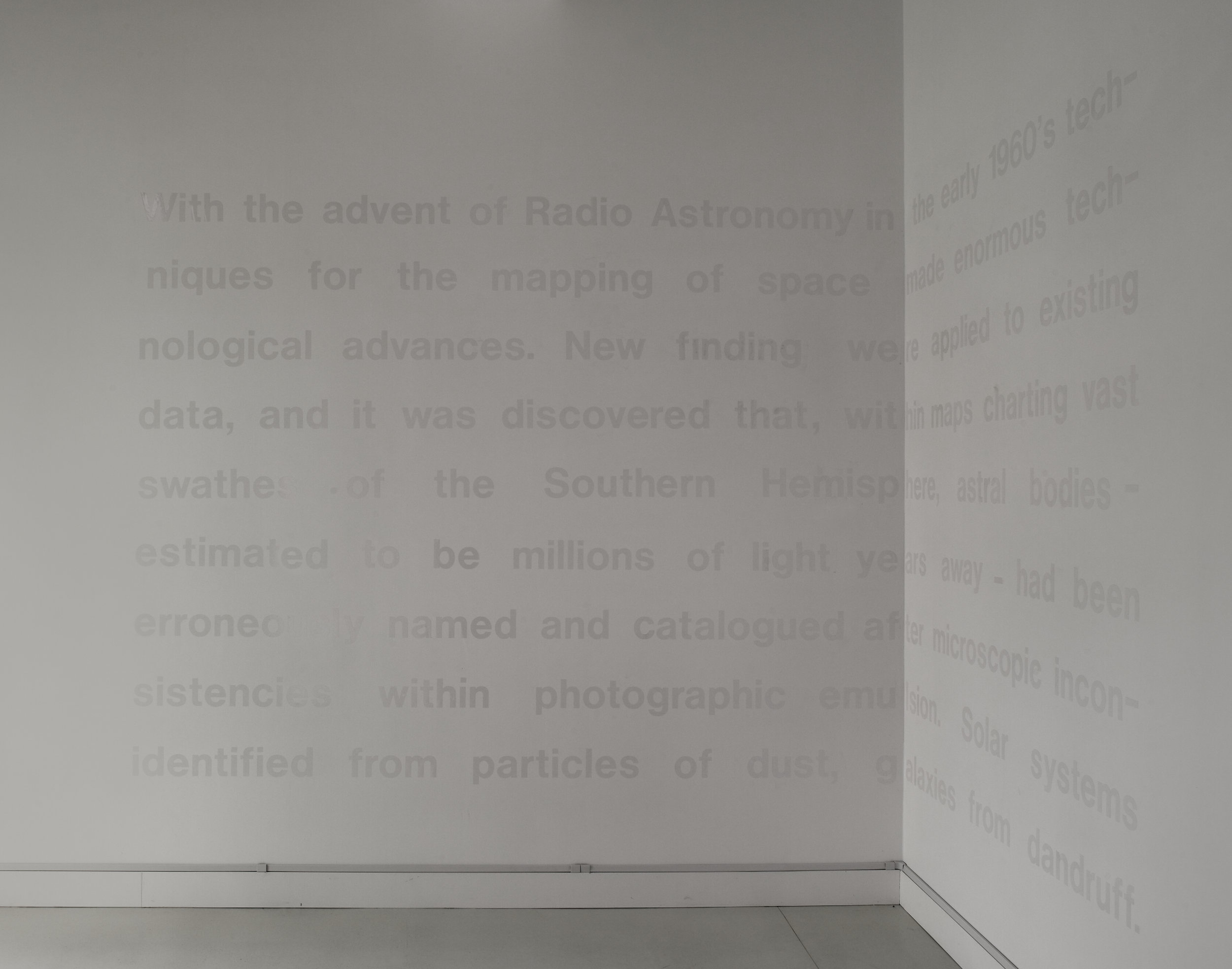

Eventually, the volume of information becomes so superabundant that it engulfs the very possibility of meaning. This is precisely the point of Anya Gallaccio's coins: signs proliferating into excess until they flow like water under our feet. Or Simon Periton's entangled doilies of signifiers, alluding to a self-reflexive galaxy of information where free-floating signifiers refer to nothing but themselves. Or Virgil Marti's over-stimulated wallpapers that tingle with nostalgia for the obviously fake.

Our compressed environment cancels itself out, like Dr Oliver Sachs' 'sleeping' patients who, it turned out, had the shakes so bad that they froze.

So Here We Are How will anyone live in the year 2000, with all that future stretched out before them? An unbearable, inconceivably vast amount of time. A thousand years can only make a human lifetime insignificant.

Not like now, not like our current preoccupation with the contemporary moment, living instant to instant, uptight in thrall to a random number, convincing ourselves that our time is special, portentous. (Millennium fever sounds so thrilling but, actually, fevers are times of stinking delirium).

As we hyperventilate in preparation for gasping in, and then indefinitely holding our big last breath late on the 31st, everything slows down until every moment seems a lifetime. Numb with over-stimulation and hyper-awareness. Every detail appears preternaturally clear, as if through a thick lens. Ultra vivid. A buzzing visual noise. A vibrancy, a self-perpetuating overload. A white noise so frenetic that it cancels itself out, becoming still. A flat chasm of emptiness.

And what would this state look like? Take a look around; you're already seeing it. Not just in artworks, but in the streets, on the tv, down the wires, crackling through the airwaves. But perhaps the epitome of this dizzying void is the work of Jason Brooks. These hypereal wreaths, so over-burdened with meaning that they become meaningless, making a mockery of meaning. Their vacuous stillness simply makes explicit what Brook's work has meant all along, that we have fought ourselves into the corner of a Möbius strip.

"What if death is nothing but sound?" "Electrical noise." "You hear it forever. Sound all around. How awful." "Uniform, white."

White Noise, Don DeLillo

(i) pacé Jean-Paul Sartre. (ii) The bulk of this essay, including the concept of simulation and the free play of signs, is indebted to Jean Baudrillard. (iii) This concept of taboo and transgression is taken from Georges Bataille.